I’m not even sure what the year was. I’d had the outline for the series for a year or two, together with a couple of chapters, I think, when Larry Shaw of Lancer asked me for a new fantasy series to follow the first two Elric books and the Blades of Mars series. This would have been in 1965 or 6, I think. I had not actually planned to write any more, but I can rarely resist a request!

My old method of writing fantasy novels was to go to bed for a few days, getting up only to take the kids to school and pick them up, while the book germinated, making a few notes, then I’d jump out of bed and start, writing around 15-20,000 words a day (I was a superfast typist) for three days, rarely for more than normal working hours—say 9 to 6—get my friend Jim Cawthorn to read the manuscript for any errors of typing or spelling etc. then send it straight to the editor unread by me. I have still to read more than a few pages of the Hawkmoon books. The odd thing is that I’ve actually read almost none of my own books but I seem to remember the events as if I’d lived them. Some scenes are better remembered than others, of course. Similarly, I’ve reread almost nothing of the Elric, Corum or Eternal Champion novels.

For fine detail I tend to rely on friends such as John Davey, who has edited several books and is my bibliographer, so he can tell me pretty much everything I want to know. In the Hawkmoon books you find some fairly thinly-disguised political satire, relating to politics of the 60s, but the main reason I made my hero a German and his base as the Camargue in France was to try to cut across some of the ethnocentric elements you found in what little fantasy fiction there was at the time and was found in genre fiction in general.

When I worked as an editor for IPC, which was then the largest periodical publisher in the world, I learned to work to crazy deadlines—hourly or daily. I found it a luxury to have a week. As is true of many who started their careers as journalists, I learned to work very fast, drunk or sober (I was sober when I wrote fiction, very puritanical about it in fact, and did no drugs at all, unless you count strong coffee and sugar. Probably the cause of later neuropathy!) to deliver decent copy on time and we almost never read our finished stuff over. I left IPC after rows involving racial stereotyping, which I refused to do, even in the WWI flying stories I wrote and you can see Hawkmoon in the light of that, too. I was determined to move my fantasy away from some kind of vague ‘time before time’ and, if you like, Europeanise it, make it relate at least to a degree to the contemporary world. My fantasy, though in all important ways essentially escapism, always has to have some relation to my own and my contemporaries’s experience of the real world or it doesn’t seem worth writing. Of course, I was primarily in those days addressing an anglophone audience, and wanted to say something like ‘Hey, we’re not always the good guys’.

I had already produced what became something of a template in the first ambitious fantasy I’d written, which became The Eternal Champion. I’d written an early version published in a fanzine called Avilion, which saw one issue, when I was 17. This was published around 1962 in Science Fantasy magazine, as a novella, and describes, if you like, the dawning revelation of a teenager who realises that his country isn’t always right, according to its own statements, and sometimes you have to oppose what you don’t agree with. Of course, I’m putting this all a bit simplistically, but I think a lot of my fiction, generic and non-generic, addresses this question, at various levels of sophistication. Essentially, it’s describing the confusion one feels when one is expected to support something which goes against everything you’ve been taught by your culture about what’s good and what’s bad. I had done a lot of questioning as a kid, though even Britain under a Tory government didn’t quite become the villainous place it became as the Dark Empire!

By 1960 WW2 was fourteen years over, many of the attitudes I was addressing were still very much in place. With my enthusiasm for rock and roll and science fantasy, my questioning of pretty much all the accepted attitudes, I was part of a generation which began what can fairly call a cultural revolution in England. By the time I came to write the Hawkmoon stories, I had already written the early Elric and Jerry Cornelius novels, had taken over NEW WORLDS and published Behold the Man, among other things. All of these tended to reject old mores and offer alternatives. Meanwhile, we had The Beatles, the new film-makers, the whole Underground press and music scenes, with which I was already identified, and all that went with the period we call ‘the sixties’ but which was roughly a period between the first Beatles single and the first Sex Pistols release (though I tend to think of the second Stiff tour as the end of the true rock and roll era!). I was playing guitar and other fretted instruments in bands through this period and I was involved in politics, especially the politics of race and gender. I was a quintessential child of my time, through which all this stuff was filtered. A band with which I would become closely associated, named themselves in reference to Hawkmoon. This was Hawkwind, who some years later would put on an elaborate stage-show and rock opera based on the Elric books. Hawkmoon, however, had fewer spinoffs than Elric, though there is still a popular role-playing game made of the novels and there have been two separate graphic novel versions.

I have to admit I remain amazed at Hawkmoon’s longevity. As I write there are current editions of his adventures in a bunch of languages, including of course the latest Tor editions , and more are appearing all the time. Not bad, I guess, for twelve days hard work! Sadly, the world hasn’t improved as much as I’d hoped (though some things are decidedly better) and a deal of what I was saying to my readers then appears to be as relevant now as it was when I was in my mid-twenties. I hope at very least that the books remain as entertaining as people found them in the 60s.

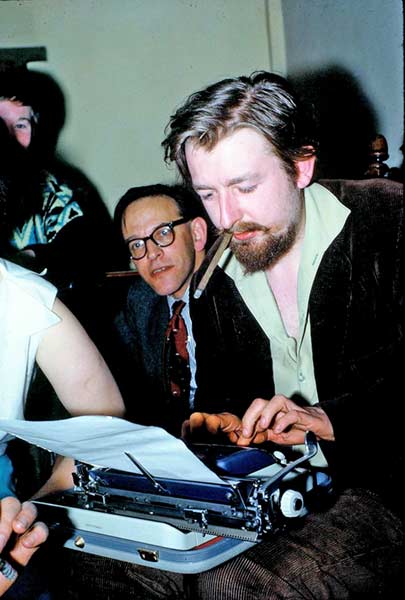

Michael Moorcock is, well, Michael Moorcock.